Camp to Crater via Disappointment Cleaver

We woke up pretty well rested to bluebird skies on day two, a very welcome change from how it looked in Paradise when we set off for Camp Muir the day before. I was also thankful to have been spared any altitude related malaise up to this point – my theory of hydrating/carb loading like you’re going to run a marathon to thwart altitude sickness seems to have proven correct once again.

Camp Muir has a surprisingly luxurious setup. I brought my inReach (a satellite communicator), but never had to use it since I was able to get decent wifi around the Gombu. A fun fact about camp is that there are actually several sets of bathroom stalls (with lights!) along the ridgeline. This was a much more refined setup compared to what we had at Baker last year, where our wag bags (human cat litter, essentially) sat baking in the sun under our tents. The toilets at Muir are “powered” by conveyer belts that activate when you pump the foot pedal five times. This separates the solid waste, which is eventually flown out by helicopter. Toilet paper is discarded in a separate container, so while you (obviously) still need to pack out your trash, this part is taken care of for you.

Another guide service had the Gombu shelter booked for that evening, so we packed up our bags and moved away from the ridgeline towards the weatherport and our tents. After settling in, we headed to breakfast where cinnamon pancakes and bacon were ready for us, along with a selection of hot drinks – everything smelled so good!

After breakfast we broke for about 45 minutes before starting glacier school. We had several lessons in mountaineering, each taught by a different guide. Grace started us off with cramponing and proper footwork – this was a refresher course after Baker and she went over duck walk and side stepping to save our calves, making sure that all points of the crampon are engaged before we move on to the next step. This is arguably the most important lesson of glacier training because all the others teach us what to do in the event of a fall, but proper footwork should eliminate the need to mitigate that risk. We also practiced walking on rocks in our crampons to the summit of “Muir Peak”- this was practice for the Disappointment Cleaver stretch of our summit bid, a two hour long traverse over rock.

After cramponing class, James taught us how to self arrest. The video that I linked introduces this concept as “a last ditch effort to correct an error in your decision making” which I love as a definition. I’m familiar with the concept but never really tried it on a steep slope. We practiced several variations, including going down head first (terrifying and not my best). Essentially you are moving your ice axe across your body and pointing the pick in first to “arrest” or stop the fall, then kicking your toes into the snow as hard and deep as you can with your crampons to stop. We learned that it’s super important not to start kicking until you are stationary with your axe planted firmly in the ground because you can tumble really bad, break an ankle, or both.

It was cool to see our whole group working together and everyone supporting each other as we learned – our crew had a good amount of mountaineering experience under their belts so everyone seemed to catch on really quickly.

Next was rope travel. This again was a refresher but incredibly important. You can either be on a short rope to mitigate risk falling off the mountain, or on a long rope in case you fall into it- the latter is used for travel when crevasses are present and the former is used for steep sections or exposure. We were all very present and engaged during these lessons, so I don’t have any photos to share from this bit.

We also practicing anchoring into a line – clipping into a line at an anchor point. This is to mitigate risk on steep sections where there’s exposure and the terrain is not ideal. I had never used this skill before and started to get a little nervous about the unknown, but the concept was simple- yell “anchor!” when you reached the clip, unclip your rope using the proper technique, and then clip in the person behind you.

After that, we practiced good spacing between team members – too much slack in the line means a risk of stepping on to the rope which could lead to rope disintegration or a tumble/fall- both not good. They told us to keep a distance of a smile between rope members. When you’re short roping, the rope can be more taut.

After ‘school’, be broke for a bit before we had “Linner” – chicken meatballs, rice, pineapple and teriyaki sauce with broccoli. Two other guides, Mike and Grace, joined us for a meal before continuing on with route finding duties. Grace carried a disco ball up the mountain to hang in the dining tent, and we all appreciated her sacrifice in pack weight for the sake of the vibe.

After we ate, we had “the talk”. Shannon and I anticipated this, as we had a very scary and stern one before Baker. The talk was basically a rundown of logisitics and expectations on summit day. Lindsay, our lead guide, took point on outlining everything that we’d be doing in the next 12 hours. We’d set alarms for 10 p.m as a wake up with a strict 11:30 pm start. That sounds like a lot of time but it’s not – we’d have to pack up our tents, eat breakfast, don all of our climbing gear (helmet, boots, crampons, harness), use the ridge bathrooms if we needed to and have packs on to go at 11:30 (we ended up starting to move at 11:24). The early start is meant to avoid crowds on the mountain. We had four rope teams and wanted to keep everyone together. Plus, the terrain deteriorates with the sun, so an early push is ideal.

Then came time for expectations. We’d be keeping a comfortable but consistent pace of 1,000 vertical feet per hour, breaking every 1-1.5 hours, with the longest stretch being Disappointment Cleaver (named because climbers once mistook it for the summit and were disappointed when it wasn’t). If you could not keep up the pace or looked otherwise weary with sloppy footwork, then you’d be told to turn around. The guides expected us to take care of ourselves on break and to be timely – making sure we were efficient and optimizing time to sit down and rest – so they gave us tricks to help, the best of which was packing your snacks in your parka pocket. The last expectation was communication and honesty – if a guide is asking how you’re doing, not only your safety but also the safety of the rest of the group depends on your transparency.

After dinner we made our way back to the tents and got our stuff prepped for summit day. We packed the following things:

-Snacks for 7 breaks (200-300 cals each) – I’ll outline food in a separate post

-Zinc sunscreen & Lip balm

-ALL layers – puffy, soft shell, hard shell (pants and top), parka

-2L of water (1L in tailwind)

-Headlamp + Backup

We crawled in our tent, but it was rough to sleep with the nerves. “Lights out” was around 5, but I barely got 1.5 hours of sleep. Uncertainty and the unknown is scary and I think it’s important to be transparent about that.

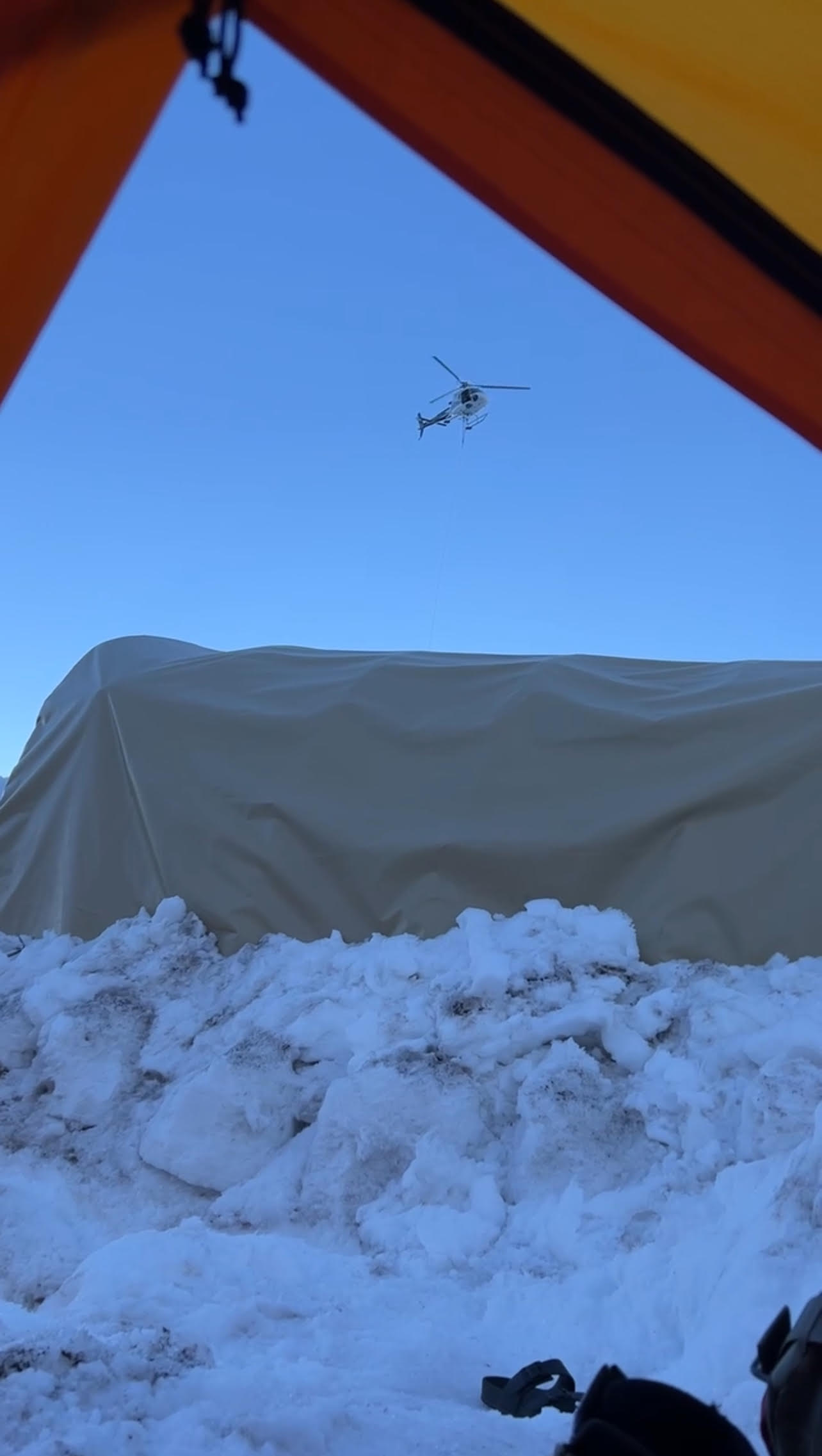

Around 9:40 p.m we woke up (the 2nd time that day!) without alarms. I peeked outside the tent and it was still light out and I heard a helicopter flying overhead and found out later that SAR was called out for a rescue.

We both hoped Lindsay would be the one to lead our rope team (though all of our guides were amazing and we’d be happy to go with any of them!) and were pleasantly surprised that she was assigned to us. We switched positions on the rope from what our original Baker lineup – this time Shannon was in the back and I was in the middle.

We started out in long rope at 11:24 p.m, 6 minutes ahead of schedule. Our ascent began on a long and gradual stretch of snow across the Cowlitz Glacier. Lindsay set a conservative pace to ensure we hit about 1,000 vertical feet per hour. I was so nervous at the start, but kept repeated Marathoner Des Linden‘s mantra: “calm calm calm, relax relax relax”. That mantra has helped to get me through Baker, Marathons, and difficult conversations with my 5 year old – v. versatile.

The cowlitz wasn’t particularly steep, and we were walking in complete darkness, which I was grateful for. There’s so much you need to think about in mountaineering and I am always very nervous to start so it was good that there was nothing to look at besides my feet.

While I consider myself spiritual, I don’t necessarily pray in the traditional way as it always felt like a personification that felt disingenuous. Something that really helps me feel connected to something greater than myself though, is by staying present – and there is nowhere in the world where I am more present than with crampons on ice. It is one step at a time, one second at a time, fully in tune and engaged with the task at hand.

I didn’t allow myself to try to digest the full climb, I just took it step by step. I concentrated on the footsteps in front of me, constantly scanning to make sure the rope had good tension and that all 12 points of my crampons were engaged before taking my next step.

Not to sound like too much of a flex, but the first stretch felt easy, my fitness felt solid and I was not having a hard time with the exertion. We traversed across the glacier to cathedral gap and didn’t stop until we hit Ingraham Flats (11,200′).

We paused at the top of the flats to take a breath, following instructions to take care of ourselves (parka, food, water, sit down on pack to rest). Unfortunately one of the members of our climbing party had to turn around at this point – grateful he was safe and in good hands with Grace, but wish Mike could’ve continued as his infectious positivity (and excellent mustache!) was such an integral part of our group.

After Ingraham, we started on to Disappointment Cleaver (DC), a 2 hour section of class III rock scramble which we had to traverse with on crampons. It went better than expected and reminded me a lot of the kind of terrain you see on some of the Colorado 14ers. Lots of hands and knees and hoisting. It was exhausting (especially combined with some sections of penitentes!) and we were all grateful to get out of there and back onto the snow.

We took another break after the Cleaver and were happy we were staying on pace and still feeling good. Downed some diy trail mix of cheez its and peanut m&ms (don’t knock it until you try it, 10/10).

The next section was very steep and crevasse heavy in parts. We were about to cross a super narrow snow bridge over a giant crevasse, and I noticed that my headlamp flashed a few times and went dim – I could barely see. I cannot think of a worse time for a headlamp to kick the bucket and I panicked a bit. I think that was the diciest I felt through the whole climb for sure, but thankfully dawn would be breaking soon and I switched to my backup headlamp after the crossing.

Next, we anchored in to fixed lines to continue on steeper and crevasse heavy terrain and it went smoothly. This was the new scary skill to unlock and I was glad we practiced it during glacier travel class- it was actually super fun and easy to clip and unclip. Had to step off the boot pack several times during crevasses which was a little uncomfortable. Used a lot of mantras and positive self-talk here about the impermanence of it all and reminding myself that after every section that was sketchy AF we’d have some kind of reprieve. Which is mostly true.

There was a section (and hopefully I’m getting the timeline right, my adrenaline was high and my oxygen was low) that we had to use our ice axes, hands and knees to navigate through on account of the steepness. Once we got through that, we paused again at High Bridge (13’500) to add layers – it was remarkably colder and windier here.

I still felt fine with the altitude, but I had to force myself to eat and drink as I didn’t really have an appetite at this point. After a bit, we were given the 5 minute break warning and Lindsay told us we were less than 800 ft to the top!!

I completely unraveled. I added to the trail of wind-swept snot that was already pouring down my face with chest heaving, gasping, ugly sobs. I knew that Shannon and I were both feeling good, holding pace, and we were going to fucking do it.

The sun finally started to rise and gave way to a sunrise that I won’t dishonor by trying to describe it with words. We could see the other prominent Pacific Northwest volcanoes- Adams and Helens – along with the Tattoosh range and what felt like thousands of layers of ice and sky and magic. I felt small and infinite in the same breath – and undone completely by the joy of it.

A few more feet and we reached the top of the crater at 5:18 a.m – the unofficial summit!!

This “counts,” they told us, but the true summit is at Columbia Crest and it was a 45 minutes round trip to traverse the crater and reach it. Thankfully, we could drop our packs and lose our ropes to get there. After celebrating and hugging the other members of our travelling party, we headed towards the ‘true’ summit. The walk to get there was beautiful and waking up with the day on the top of mother mountain felt like magic.

When we got to Columbia crest, we took a few summit photos and signed the register, congratulating other climber strangers who were at the top.

A few minutes went by before Cassidy let us know we had to make our way down. We bumbled down towards the rest of our climbing partners, crying, cackling, and celebrating being alive. The statistic is that only 50% of prospective summiteers make it to the top of Rainier, and gratitude echoed through my body at our blessing – I truly wish I could bottle up the joy exuding out of us in those moments.

Being a bluebird day after a few days of bad weather meant that the mountain was packed and Lindsay wanted to get us moving to avoid the traffic – we were all excited to see the route with the aid of some light! I’ll be outlining the descent with some great daytime footage in my next post — subscribe below to get notified when I drop the next section!

Leave a comment